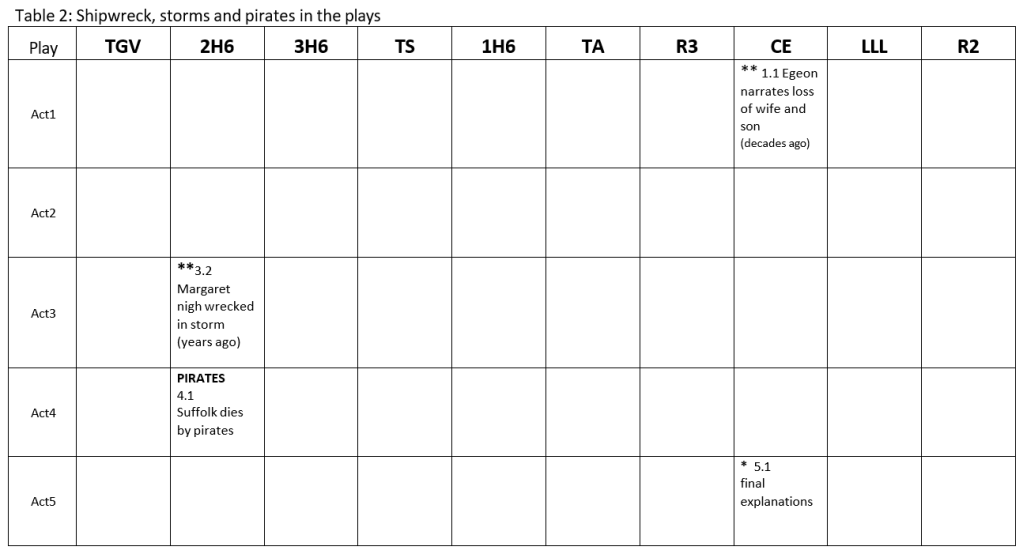

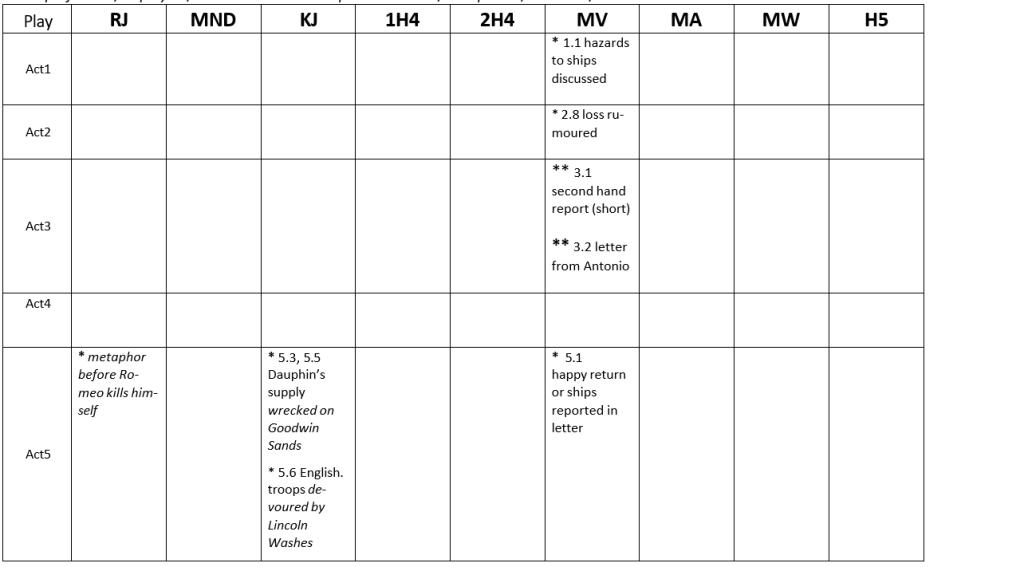

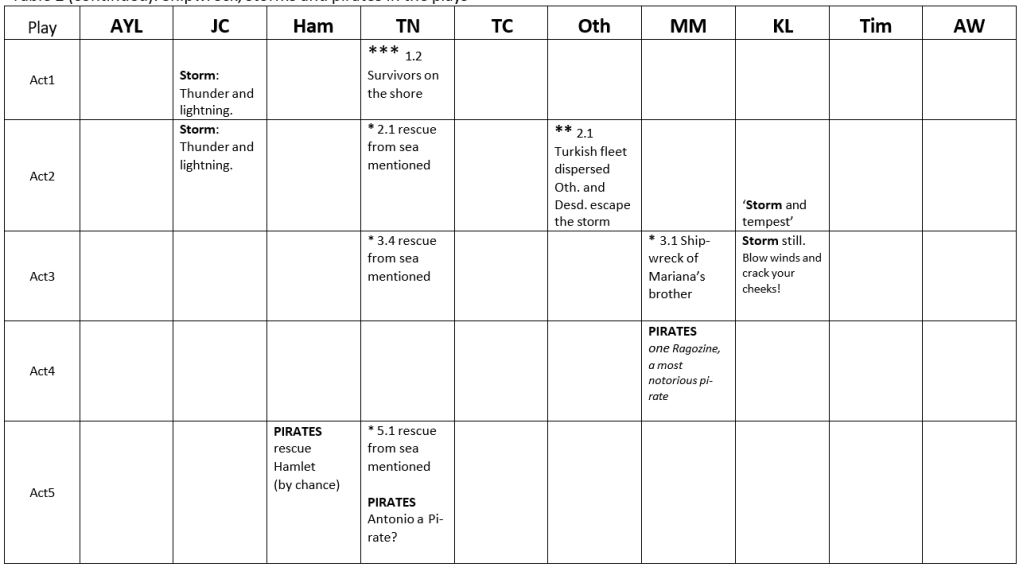

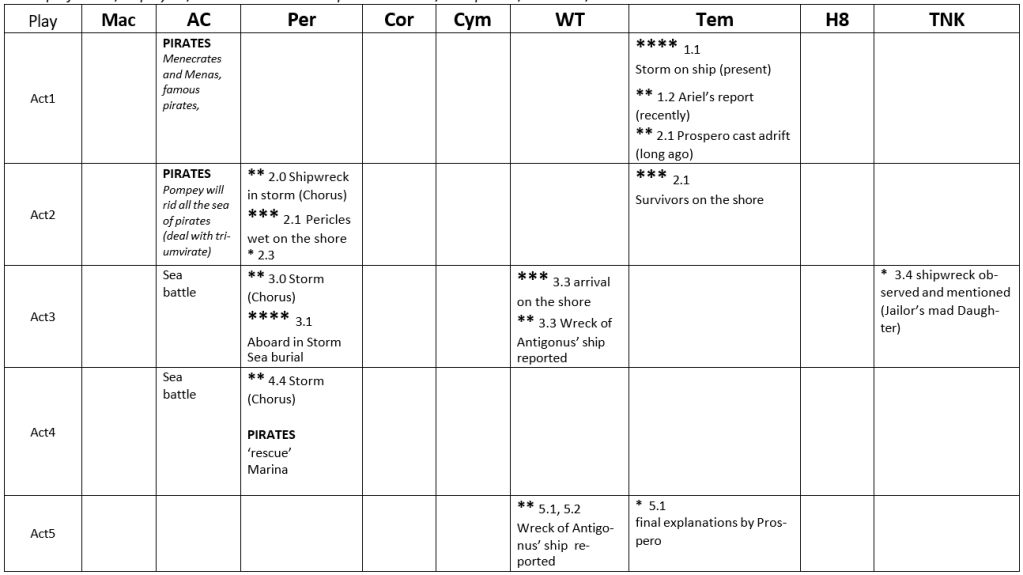

To begin with the latter issue it can be observed that the primary function of shipwreck in the plays is not to cause death and destruction, but to separate main characters, as many observers have stated.[i]

A fatal outcome is very much the exception. Of course, there is the sinking of Antigonus’s ship off the coast of Bohemia in The Winter’s Tale, which prevents any news about Perdita reaching Sicily. And there is the destruction of the Turkish fleet in Othello. All other shipwreck victims not only survive, but stay unharmed.

It has been observed that the plots of Shakespeare’s plays are basically fuelled by separation or by conflict. Any plot has to involve characters in whom the audience is in some way interested. This can be achieved by changing the conditions or relationships in which characters are presented. The goal is that the ‘audience, or reader, wishes … to see [the situation to be] changed, or to remain unchanged’.[ii]

In the plays involving shipwreck, we have to wait for the protagonists to be reunited. Usually, any reunion will not happen directly or easily, but only after some ‘swerving’. In any case, the shipwreck will foreground or create relations between people and situate them in space.[iii]

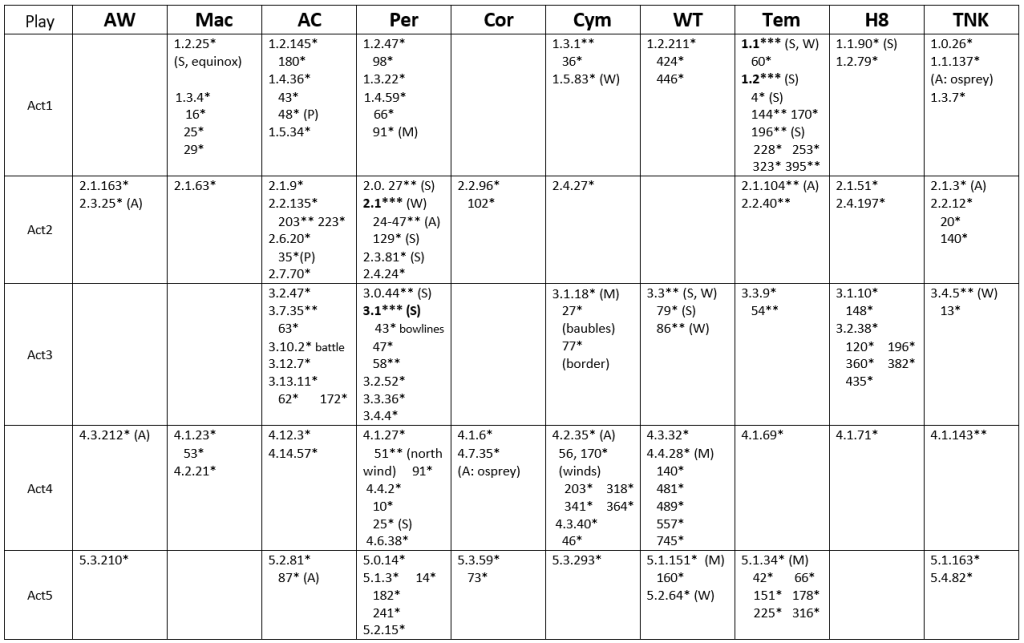

Now to the first part of the question: one must be able to afford to be shipwrecked in the first place. All the farmers and shepherds we meet where they live. But if we list all the persons shipwrecked (or captured by pirates) in the plays, we get an impressive line-up, which gives sea travel and shipwreck quite an upper-class tinge and allure (like reading aristocracy reports in the tabloids):

- the king of Naples and his entourage

- Hamlet, prince of Denmark

- Pericles, a prince of Tyros

- Margaret, a princess

- Othello, a general

- Viola, a lady, daughter of Sebastian of Messaline (a merchant? an aristocrat? … certainly rich)

- Egeon, a merchant of Syracuse (probably rich) and his family

- Antonio, a rich merchant in Venice (doesn’t travel himself, but sends his ships)

- Antigonus, a courtier

The leading characters of the play, which are separated by shipwreck, certainly are upper-class. The sailors and ship crews, for whom storms and shipwrecks are part of the occupational hazard, are rather treated as by-catch and hardly ever mentioned. Only in The Tempest is care taken to stow them safely below the hatches, and in Twelfth Night they provide the ‘minor characters’ of the mariners helpful to both Viola and Sebastian.

[i] Morrison, 2014, Shipwrecked, p. 35;

Stafford, 1966, ‘Shakespeare’s Use of the Sea’, p. 49;

Jones, 2015, Shakespeare’s Storms, p. 2;

Schalkwyck, 2019, ‘Storms and Drops, Bonds and Chains’, p. 67.

Snider, 1874, ‘Shakespeare’s “Tempest” ’, p. 198: shipwreck is ‘an artifice of the poet for scattering, or possibly uniting, his characters in an external manner’.

[ii] Williams, 1951, ‘Shakespeare’s Basic Plot Situation’, p. 314. Williams identifies ‘unnatural division’ as the driver of the plot in the comedies and lists following examples:

- ‘the unnatural resolve of the men in Love’s Labour’s Lost to separate themselves from womankind;

- the abnormal, if accidental, separation of twin brothers in The Comedy of Errors;

- the unnatural and abnormal separations of husbands and wives in All’s Well that Ends Well, Cymbeline, and The Winter’s Tale;

- the abnormal enmity of brothers, and the physical banishment of three of them, in As You Like it and The Tempest …

Only The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Merchant of Venice do not conform to the pattern.’ Williams provides a similar listing for the tragedies.

[iii] Habermann, 2012, ‘ “I Shall Have Share of This Most Happy Wreck” ’, p. 59.